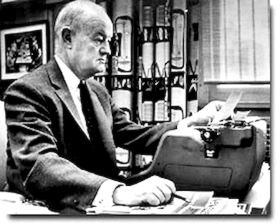

John S. Knight of The Akron Beacon Journal

By Robert H. Giles The Nieman Foundation

In 1967, John S. Knight was 73 years old and still writing The Editors Notebook, a Sunday column he had started in 1930 at the Akron Beacon Journal, which now reached a national audience.

The notebook was where JSK spoke his mind with blunt honesty, often to the discomfort of his social peers at the country clubs and business peers in the boardrooms. Writing the notebook was a ritual we observed every Thursday at the Beacon Journal. At precisely 9 a.m., Knight would stride purposely through the newsroom, dressed like a banker, jaw set for action. He entered his office in the corner of the newsroom and closed the door. There were no interruptions, except at noon when his secretary, Lillian Brenner, would deliver a hot dog from a sandwich shop across the street, kept warm in a silver service. At 3 p.m. the door would open and Jack would emerge, copy in hand, ready for discussion and editing.

In August, Knight was one of 23 Americans appointment by President Johnson to observe the national elections in South Vietnam. He was the lone opponent of the war in the group. If LBJ thought the experience would soften his criticism, it did just the opposite. Gene Patterson of the Atlanta Journal and Constitution initially thought Knight was just a dove. "But I was wrong," he said later. "He was a journalist, always probing for fresh information and new insights."

Back home, he denounced the rise of anti-intellectualism as a corrosive side effect of the war. "Although the right of dissent is clearly set forth in our Bill of Rights," he wrote, "there are those who would deny this right to others who view U.S. involvement in Vietnam as a grim and unending tragedy."

Knight's vigorous defense of free speech angered the powerful pro-war factions that wanted to smother dissent. And they could not understand how this editor, a man of elegant taste and old-fashioned virtue, could take the side of rebellious youths who smoked pot and wore the American flag on their tattered jeans. To his critics, he replied, "As an opponent of our involvement in Vietnam since 1954, I have neither enjoyed criticizing three presidents nor accurately predicting the consequences of their policies." When the Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing was awarded to Jack Knight the following May, the Pulitzer Board noted the clearness of style, moral purpose, sound reasoning and power to influence public opinion.

For this plain spoken Ohio editor, by then a national figure as chairman of Knight Newspapers, the prize was an affirmation of the virtue of speaking one's mind with clarity and honesty.

This was a "leadership moment" presented at the ASNE Convention April 3, 2001, at the J.W. Marriott Hotel in Washington, D.C.