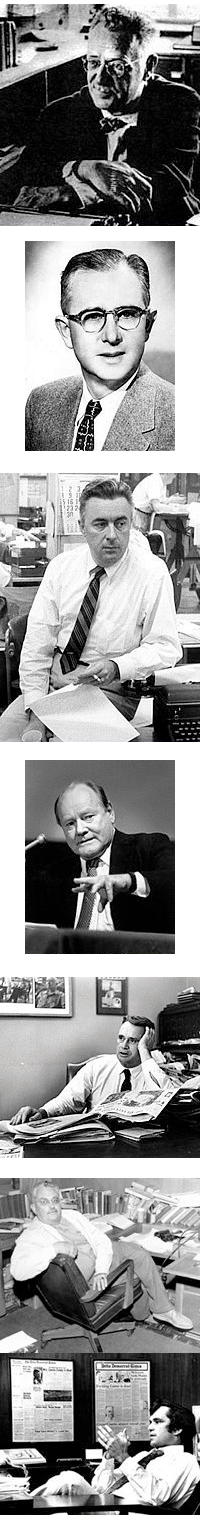

Civil Rights Era Editors

By Eugene L. Roberts University of Maryland

There may never have been a time in national history when a small group of editors became as important or as influential as in the South during the Civil Rights Era.

The region’s political leaders, the vast majority of the South’s governors, senators and U.S. representatives played politics with the Supreme Court school desegregation decision, questioning whether it even had to be obeyed. A handful of Southern editors, probably no more than 20 at peak, placed the national interest above regionalism and argued that if the Supreme Court was not obeyed, anarchy would descend upon the country. Through editorials or columns, these editors spoke out and became voices of sanity in a period of political abdication from national responsibility. They were at odds with most of their readers. They risked advertising and reader boycotts. But they were forceful and often eloquent.

When political leaders like Harry Byrd of Virginia advocated closing schools to avoid school desegregation, Jonathan Daniels of the Raleigh News & Observer reacted with style. He noted that this -- closing schools -- might be worse even than what had befallen the nation during the Civil War. Because closing schools, he said, was something beyond secession from the Union. It was, he said, secession from civilization.

Editors like McGill, fearful at times that they were years ahead of their readers, denied that they were integrationists, only believers in the law. But ultimately, McGill said he was for integration, not just because it was the law but because it was the right and just position to take.

The editors took great risk. Hazel Brannon Smith watched the financial health of the Lexington Advertiser in Mississippi decline precipitously after she protested the sheriff’s shooting of a black man for making too much noise. The boycotts against her increased in intensity when she editorially attacked the white citizens council.

Ira Harkey, Jr., editor and publisher of the Pascagoula Chronicle in Mississippi became a pariah in his town and, ultimately, felt compelled to sell his newspaper. His offense: he opposed Governor Ross Barnett’s stop-at-nothing approach to preventing the desegregation of the University of Mississippi. A bullet pierced the door of his newspaper; a shotgun blasted out a window of his home; a cross was burned on his lawn, but Harkey said in an editorial, “Ah Autumn. Falling leaves, the smell of burning crosses.”

Humor, even in the toughest of times, kept the editors afloat. Two of the most courageous editors were father and son, Hodding Carter, Jr. and Hodding Carter III of Mississippi’s Delta Democrat Times. They never lost their ability to laugh or their sense of outrage at racial injustice, particularly the organized brand pushed by the white citizens councils.

After Hodding Carter, Jr. wrote an article for Look magazine detailing the dangerous menacing spread of a white citizen’s council, the article was branded on the floor of the Mississippi House of Representatives as a quote, “Willful lie by a nigger-loving editor.” And the House then voted to censure Carter. Carter’s reply in a front-page editorial was a classic. It said,

When it became popular among racists to refer to Ralph McGill as “Rastus Ralph,” McGill fought back. He named his little dog Rastus and trained it to bark whenever a telephone receiver was pointed at it. Thereafter, when he received harassing phone calls at home, McGill would say, “So you want to speak to Rastus?” and point the receiver at the dog and the dog would bark away.

The outcome of the civil rights struggle might have been different, and almost certainly, the South’s resistance might have even been more violent, had the editors not provided leadership at a crucial time.

In addition to the editors I named, there was Lenoir Chambers of the Norfolk Virginian Pilot; Sylvan Meyer of Gainesville Georgia and the Miami News; Coleman Harwell and John Seigenthaler of the Nashville Tennessean; C.A. “Pete” McKnight of the Charlotte Observer, Bill Baggs of the Miami News; Caro Brown of the Alice, Texas Echo; and John L. Harrison and Horance G. Davis, Jr. of the Gainesville Sun in Florida.

And let us remember, too, the editors of black weeklies like Emory Jackson of the Birmingham World in Alabama and Daisy Bates of the Arkansas State Press. They believed the time had come to end segregation in America. And they struggled fearlessly to hasten the end.

Think of the consequences if the Southern editors had not stood up and reached out to the rest of the nation, even at the risk of angering their readers and touching off reader and advertising boycotts. The gulf between the South and the rest of the nation might have grown wider. A stormy period in our nation’s history might have become even more stormy. Instead, segregation came to an end and our nation entered into a period of reconciliation.

Thank you.

This was a "leadership moment" presented at the ASNE Convention April 3, 2001, at the J.W. Marriott Hotel in Washington, D.C.